I became interested in this question a long time ago. I brought it up in my JET Programme interview, to the Harvard Kennedy School when trying to justify working there for a year before starting school, and to just about every person I met in Japan (after establishing a rapport). After a year in Japan and a long time concerned with refugees, here's what I found.

What's the problem?

Japan is an aging society. Longevity and low birth rates have led to a much larger ratio of people relying upon government benefits to people working to pay for them; benefits programs have doubled as a share of GDP in the last 30 years alone. On top of this, Japan has a huge debt burden. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe's proposed economic solution, raising the consumption tax from 8 to 10%, has so far done more harm than good.What Japan needs to do is increase production--a very simple way to do this is by adding people to the workforce. Japan's aforementioned low birth rate means this will have to be foreigners. This is where refugees come in.

Amnesty International says there are currently 22 million refugees. On top of this, 10% of refugees need to be resettled every year because of outbreaks of violence, insecurity, or xenophobia. More than 80% of refugees today are hosted in developing nations despite the fact that developed nations, like Japan, have a far greater capacity to host refugees.

In Japan's case, there is even a huge need for people. Right now, foreign workers make up 2% of Japan's labor force. For most developed countries, this number is around 10%. In the US, the world's largest economy, that number is above 17%.

What is Japanese immigration like now?

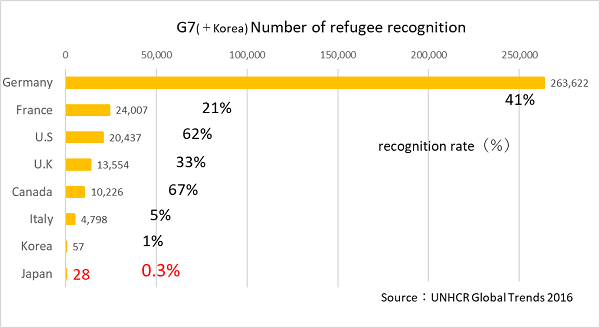

Complicated. But hey, at least the whole country isn't closed off to the outside world anymore. In 2017, Japan received 20,000 applications for asylum and accepted 20. At the height of the Syrian refugee crises, Japan accepted just 7 Syrian refugees (from 2011 to 2016). In 2018, the number of accepted refugees doubled to 42, though compared to the 16,269 people who were deported the same year, this change is kinda insignificant. What is also interesting is that the number of applicants also dropped by half--to around 10,000--in 2018. Why is that?The reason is that Japan's refugee/asylum system has long served as a back channel for those hoping to immigrate to or work in Japan. Many economic migrants applied for asylum to take advantage of the 6 month work privilege. "Filipinos accounted for a quarter of the applicants. Conflict zones in the Middle East and Africa — Syria, Afghanistan, Congo, Iraq, Yemen, and South Sudan are some of the usual countries UNHCR expects to see — accounted for only 1%." This was not intended. Japan cracked down in 2018, but did not fully solve the problem.

Another complication is the human rights abuses in the migrant labor system in Japan. The main culprit is the Technical Intern Training Program (TITP), which allows unskilled 'interns' to come to Japan and work. However, "While some interns aren't taught any skills, others experience forced labor conditions including having their passports confiscated, being given arbitrary salary deductions, being confined to particular accommodations, being prevented from communicating with anyone beyond their colleagues, with some paying up to $10,000 to participate in the program.” Essentially, this is how Japan uses and abuses cheap labor without a functional immigration system. There are 230,000 people in the program today.

There are more problems with this system, like the extremely narrow definition of a refugee Japan uses, the racism/xenophobia, the years and years of wait times, or the abysmal treatment of migrants, but I believe these are the main barriers affecting the system at a large scale.

What could the system be like?

While there is still a huge unmet global need, there are some good examples that could provide a model for Japan. Canada is the current world leader for sheer numbers and many countries have raised their quotas in recent years. On top of this, there are times when Japan itself was a model to follow. In the wake of the Vietnam war, Japan took in more than 10,000 refugees who fled from Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia.

While there is still a huge unmet global need, there are some good examples that could provide a model for Japan. Canada is the current world leader for sheer numbers and many countries have raised their quotas in recent years. On top of this, there are times when Japan itself was a model to follow. In the wake of the Vietnam war, Japan took in more than 10,000 refugees who fled from Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia.However, even if Japan suddenly overcame the massive popular hesitation around foreigners and refugees, the numbers would not be spectacularly high. As alluded to above, very few applications in the refugee system actually come from people in need worldwide. There are three main reasons for this: lack of social networks (migrants tend to go where their friends and family have gone), unfavorable labor laws (see 過労死 karoshi), and Japan's intentional barriers to entry such as a mandatory 6 to 9 month orientation course. In short, without a campaign to raise application rates to Japan, estimates range from 50 to 2,000 people would come as refugees each year. Though the high end is more refugees than Japan has accepted since singing the UN Refugee Convention in 1981, it is not nearly enough to make up for Japan's labor shortages.

Conclusion

Refugees alone will not solve Japan's aging problem. That's because there just aren't enough of them. However, each additional refugee admitted to Japan will be a life greatly improved and a step towards addressing the labor shortage; it's still a win-win to accept more refugees. This raises the question, what will solve this problem?One suggestion is to expand the immigration system more generally to accept migrants of all types. Of course, this should be done in a much different way than the abusive system that exists now. However, some estimate that even expanding and reforming this program would only be a drop in the bucket. A major overhaul would be needed to the sheer numbers needed to properly address the labor shortage. This means sweeping liberalization of the system and massive increase in support throughout society.

But what if the problem is not labor shortage at all? Of course, the aging of the population is certainly one half of the equation, but the other half is declining birth rates. On reason for this decline is the pressure Japanese society puts on young people and women. Japan has some of the longest working hours in the world and many problems surrounding contractual employment that inhibit young people's ability to start families. Japan ranks 161st out of 193 countries in female political representation. Women in Japan make up just 13 percent of managerial positions (compared to 44% in the US). Socially, harassment of working mothers is so common it has its own word (マタハラ matahara from 'maternity harassment') and women are sometimes forced to apologize for becoming pregnant out of order (senior women go at more convenient times). Every country has its problems and the Japanese labor problem is certainly complex, but I believe it is reasonable to hypothesize that reducing barriers for young families and fully utilizing the potential of women could huge positive effect on this and other problems.

At the risk of further complicating the issue, I have to admit that my own experience in Japan does not fully confirm the data and research above (specifically this survey). Though there was certainly a lot of apprehension and concern for safety and crime, almost every Japanese person I talked to thought that Japan could and should do a better job of accepting refugees--especially after we talked for a while. There was a genuine, widespread sense of international duty and a willingness to do the right thing. True, it may be easier to give your true opinion to a Japanese surveyor than an actual foreigner in the flesh. Another interpretation is that, maybe, this is a larger conversation that, once enough people have had it, could move Japan in the direction of accepting more refugees.